Many years ago, when I was learning about “command languages” used in online search tools such as DIALOG and BRS, I recall asking about certain strange (to me) groups of characters that made no natural-language sense to me, the first time I saw them. They appeared in only one of the databases we searched. My professor, a search language guru, explained: “Those are reserved codes used in the Oil & Gas industries. And nowhere else,” she intoned with the voice of wisdom and experience.

Since the advent of generalized search engines – such as Google, but in fact there were several good ones around a few years before that – everyone knows (or think they know) about the basics of searching for information via their computer and a browser.

Scientific search, by contrast, is a specialized corner of the search industry. When the literature of your subject discipline entails such aspects as a controlled vocabulary (possibly including taxonomies and ontologies) and other discipline-specific metadata, as a researcher and author you are probably better served by a semantic domain-aware search tool.

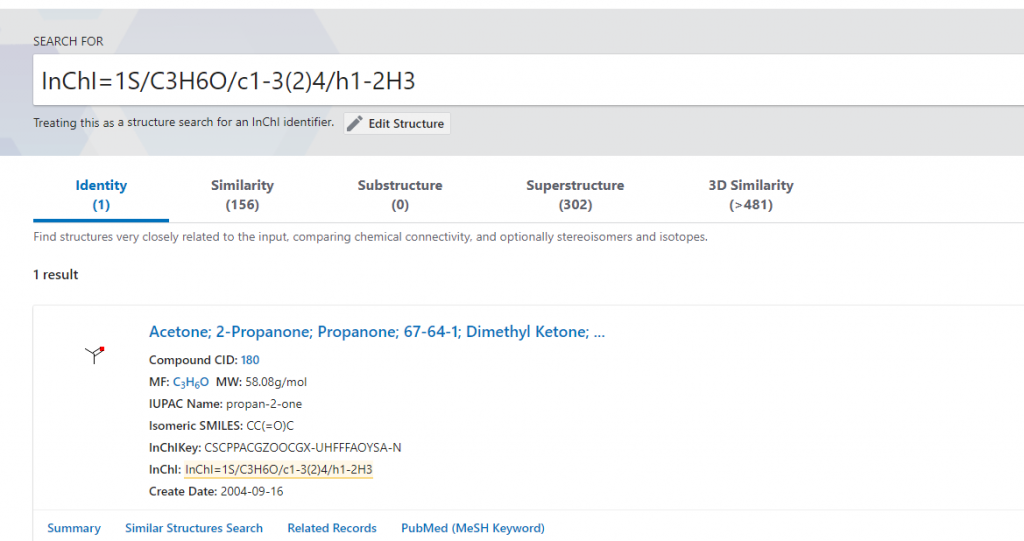

For Example: A screenshot from NLM’s PubChem search utility:

Note: Although I used an example from chemistry, one could as easily look to Physics or Geology. There are probably as many discipline-specific tools as there are scientific domains.

It follows that a search tool optimized for organic chemistry is not likely to work well at all when applied to questions in quantum astrophysics. They are not, as the idiom has it, “talking the same language.” One approach, however, that is useful across disciplines is that known as “semantic search.” Semantic search basically describes a cluster of techniques that enable the algorithms of a search utility to probe a dataset for concept correlations (words and phrases traveling together) and, from these, to draw reliable inferences about ‘hidden’ relationships lurking in the text. It is an interesting angle, I think, because it goes beyond the simple “type in a bunch of keywords and hope for the best” tactic that most of us use, and it applies those semantic techniques to get more relevant results, more quickly, when the datasets include predefined scientific concepts. It’s something I have been interested in (at a distance) for a while.

While I’m not in contact with my old prof. anymore, I wish I were so we could sit down over coffee and discuss the brave new world these new tools may open.