As I wrote in my earlier post, CCC is pleased to offer a new ebook, “Creating Solutions Together: Lessons to Inform the Future of Collective Licensing.” We published it with the overall purpose of providing the reader with an introduction to some of the “whys & hows” of collective licensing, the general origins of collective licensing as a business model, and specifically about how CCC was established to help licensees access high-value content while ensuring appropriate remuneration back to publishers and other rightsholders. You can read and download it here.

With that goal in mind, CCC called together three leading copyright and licensing experts, Lois Wasoff, Mark Seeley, and Bruce Rich, to contribute essays to the ebook. Today’s blog post focuses on the first essay in the collection, Wasoff’s “Publishing as Embodiment of Licensing.”

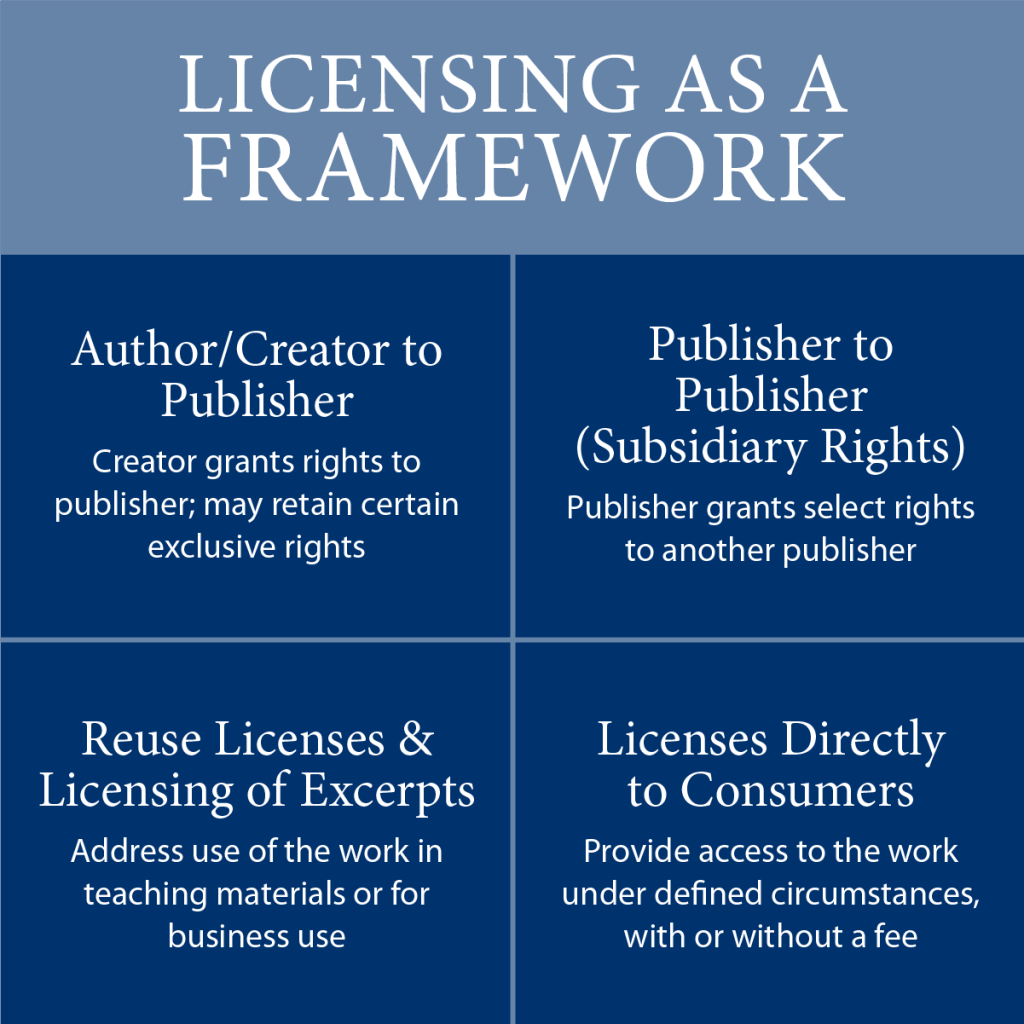

Wasoff herself is certainly well-acquainted with all aspects of the publishing business, having spent nearly her entire career as an industry lawyer, including a dozen years as vice president and corporate counsel at the prominent Boston publisher Houghton Mifflin Company. In her essay, she introduces the concept of “publishing as licensing.” That is, beyond the role of a publisher as a printer and distributor of books and other such materials — a role typically subcontracted out by most publishers to specialists in their fields — it turns out that publishing is all about licensing. Publishers receive rights from authors and other creators (such as photographers and graphic artists); they then exercise those rights in a variety of ways that may result in physical books and journals but also in other expressions through which the copyrighted works will generate revenue, buzz and perhaps reputation for the authors, the publishers and anyone else associated with them. Almost all the ways in which those rights are transferred and exercised are licensing and sublicensing transactions, and once the author enters into an agreement with the publisher (which is largely a licensing transaction), most of those other activities are the responsibility of the publisher to manage.

As Wasoff writes, “’Publishing’ and ‘licensing’ are not separate concepts; publishing is a particular species of licensing, with its own increasingly varied industry practices that have evolved to meet the constantly changing needs and expectations of that reader/user we first mentioned.” Deeper in the essay, Wasoff points out that “Historically, written works reached their readers through the sale of physical copies. Licenses were, for that reason, primarily a tool that authors and publishers used to define their relationships with each other. Copyright law, not license terms, defined the rights and privileges of most readers. Digital distribution has dramatically changed that paradigm. Licenses now increasingly define the relationships between authors and publishers on the one hand and their customers on the other.” This is a very important point.

Deeper in the essay, Wasoff points out that “Historically, written works reached their readers through the sale of physical copies. Licenses were, for that reason, primarily a tool that authors and publishers used to define their relationships with each other. Copyright law, not license terms, defined the rights and privileges of most readers. Digital distribution has dramatically changed that paradigm. Licenses now increasingly define the relationships between authors and publishers on the one hand and their customers on the other.” This is a very important point.

Wasoff’s core insight, that licensing is – and has long been — the very embodiment of publishing, adds powerfully to the conversation around the 21st-century role of publishers and their (various) audiences. Authors and other creators may come to a new perspective about their relationship(s) with publishers; publishers may be reminded that they are users of rights too (that is, that they act as both (sub)licensors and (sub)licensees in almost all parts of their businesses); and readers may come to a greater appreciation of the multiple layers of licensing work that must oftentimes be completed before a new book or article reaches them. These are insights that are conceptually useful, no matter where you happen to find yourself in the copyright ecosystem: author, other creator, publisher, re-publisher, or reader.