In my previous post here, we touched on the critical importance of peer review in scholarly and scientific publishing, as well as the inefficiencies that are still part of the process. This criticality has only been heightened during the “rush to publish” times brought about by COVID-19. From preprint servers spilling over with works not vetted for quality to the massive volume of new papers , there is no end to the material that has to be screened, read, assessed and – if appropriate – applied to critically important, life–saving work.

The core of the scientific communications ecosystem is to pursue two basic questions: How do we discover new and useful science; and —once someone claims to have discovered something new— how do we know whether this is true? To answer these questions, we apply expertise and technology to help us quickly produce papers of high reliability and quality so we can release them to the community for consideration and evaluation. We see some movement towards this already:

- A recent (July 20) article in The New York Times discusses “How to Identify Flawed Research Before It Becomes Dangerous” through increased, judicious, use of preprint servers.

- In an article in IEEE Spectrum, we learn about an experimental AI program used to blitz through the initial stages of peer review, for large numbers of submissions, at very high speeds.

- An article in JAMA highlights the difficulties of “Communicating Science in the Time of a Pandemic,” including such issues as reporting on incomplete studies, out-of-context results, and inadequately reviewed studies. In a related piece, the JAMA editors emphasized, once again, that peer review is critical.

In developing the Scientific Publishing Ecosystem map with Outsell last year, our research further confirmed my view that semantically enriched metadata can and should play an important role in improving and expediting the scholarly publishing cycle, while also helping to ensure that the articles involved adhere to the highest possible standards of quality and reliability. Without normalized metadata, the approaches described above are helpful, but on their own, don’t go far enough to address the broader challenge.

Publishers who embrace strategic data management throughout the entire publishing lifecycle are easing the inherent stresses of publication workflows while reducing operating costs. Scientific and scholarly presses were busy before in defining and managing their transitions to open science ; and now are under enhanced social and audience pressure to produce in response to COVID-19. Curating your data is a necessary first step for most research projects adhering whenever possible to the FAIR principles of findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable.

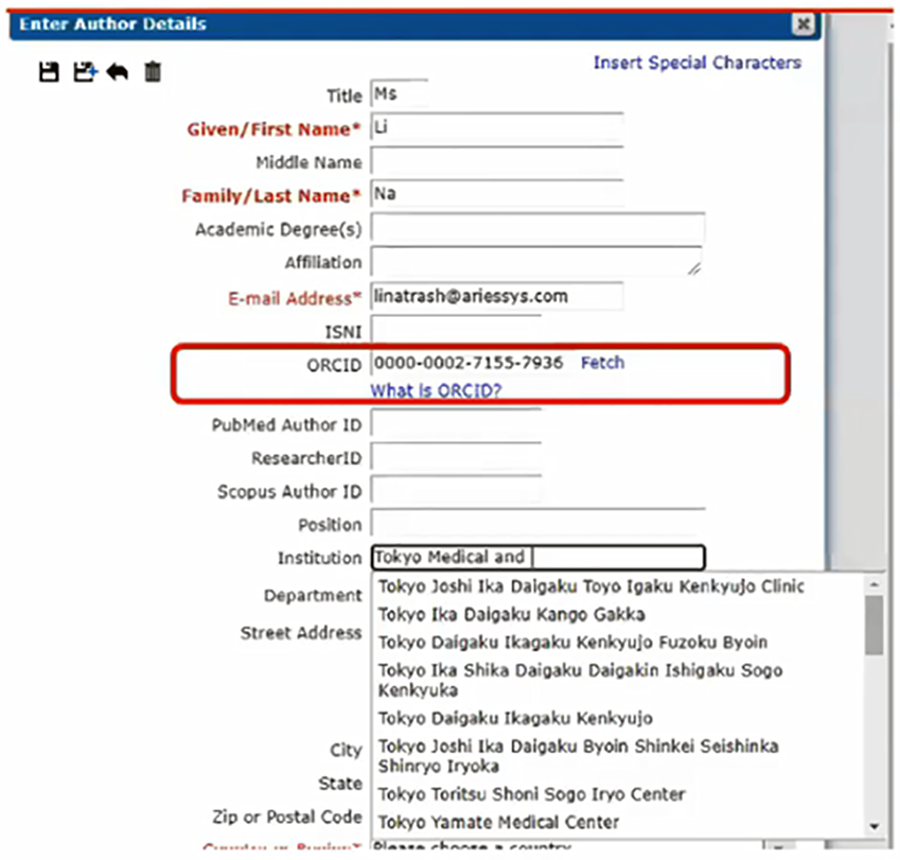

With this context in mind, let’s take a look at some of the points raised in a recent webinar, co-hosted by Aries Systems and CCC, “Streamlining OA Workflows.” Early on, CCC Presenter Andrew Robinson brings up the usefulness of “persistent standard identifiers” which function as metadata about the persons involved (author or creator), the transformative agreements in place, as well as the work and the journal (or other such publication). As he said in the webinar, “these solutions require data-driven, collaborative, and transparent approaches.”

Over the course of the interviews and survey we did in putting together the Scientific Publishing Ecosystem map, we heard several times that the community needs to elevate the importance of standards data in the research continuum, beginning at the step of authoring and continuing through to knowledge creation and consumption — which in turn leads to new work and new knowledge. Articles exist in a network and are often consumed by machines. Making the network more efficient and effective through the use of persistent standard identifiers adds value to science and aids discovery. It also ensures the highest levels of quality for these research outputs.

Data-driven, collaborative, and transparent: these terms describe what is essentially our mission going forward. As the editorial team for Nature wrote in April, “There is no business-as-usual during this uniquely challenging time.” For science in the time of COVID-19, we need to continue to invest in improving data throughout the lifecycle, streamlining our processes, and making it easier for the community to access and validate research.